oHneH Microfactory

Knitwear Studio

oHneH – Microfactory by Mone Unmüßig

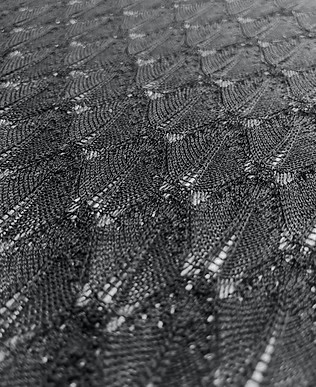

Mone Unmüßig runs the microfactory oHneH in Hamburg, where she creates unique, custom-made knitwear pieces for high fashion labels. Her work is highly individual, meticulously crafted, and exudes a haute couture aesthetic – a combination of creative ambition, technical finesse, and deep understanding of textile structures.

Our Services

1. Knitting Services

We specialize in the production of high-end knitwear, offering both fully fashioned and cut & sew techniques. Our in-house programming allows for the development of customized knitting instructions tailored precisely to each design concept.

-

Fine gauges available: 7gg, 14gg

-

Fully fashioned and cut & sew production

-

In-house linking (kettling), external sewing and finishing

-

Yarn sourcing consultation and technical support

-

Flexible production models: full-service manufacturing, OEM/contract production, sample development, and prototyping

-

Minimum Order Quantity (MOQ): 30 pieces per design

2. Machinery & Technical Capabilities

Our microfactory is equipped with cutting-edge Stoll ADF technology, enabling advanced design techniques and exceptional flexibility:

-

Stoll ADF Ki 7.2 multigauge and Stoll ADF 32 W 7.2 multigauge

-

Capable of reverse plating, intarsia plating, weave-in technology, and IKAT plating

Yarn Specialization

We work primarily with natural and regenerated fibers and are experienced in handling delicate and complex yarn compositions:

-

Merino wool and blends

-

Cotton and blends

-

Wool blends

-

Mohair blends

-

Alpaca

-

Viscose

-

Cupro

-

Silk

-

Technical fibers

3. Product Diversity & Collaboration

At our microfactory, development is approached as a co-creative process. We support fashion labels from initial concept through to the final knit product, combining technical expertise with a refined design sensibility and a deep understanding of textile engineering.

What sets us apart is our commitment to bespoke, collaborative partnerships. We listen, anticipate, and contribute our extensive experience in fashion design, pattern construction, and industrial knitting processes. Whether you're working in womenswear (DOB) or menswear (HAKA), seeking the experimental or the timeless – we co-create knitwear that is technically sophisticated, aesthetically distinctive, and couture-inspired in execution.

Contact

oHneH & oHneH microfactory

Billbrookdeich 186

22113 Hamburg,

Germany

contact person: Mone Unmüssig

Languages: German, English

Mail: was@ohneh.com

phone: +49 (0) 1736604306

Mone Unmüßig

Mone Unmüßig is a designer, knitwear technician, and founder of the label oHneH. With her MicroFactory in Hamburg, she is pioneering new approaches to fashion production – local, high-quality, and collaborative. In this interview, she talks about her self-taught passion for knitting, the unique qualities of Hamburg’s fashion scene, and why she hopes that fashion will always leave room for dreams.

You run two businesses – your own label oHneH and the MicroFactory. How did that come about?

It actually came about quite naturally. I had been working as a designer for many years, and over time I developed a strong interest in industrial flat knitting machines. The two paths eventually merged organically. That’s why it doesn’t feel like two separate businesses to me – my label oHneH and the MicroFactory simply belong together.

The starting point was really the desire to own such a machine. Even before I ever used the term “MicroFactory” – which wasn’t common at the time – I already had the vision of producing my collections myself and managing the entire production process independently. The idea of local production has always been close to my heart and is deeply rooted in my craft-based background. I’ve always enjoyed working directly on the product, and this setup allows me to do just that.

Creatively, it’s incredibly enriching for me to be so close to the technology. The more I learn about processes, machines, and technical details, the more diverse and exciting my design work becomes. Knowing how something is made automatically leads to new creative ideas – and in my eyes, that not only makes the products more beautiful, but also more coherent.

And how did your first commissions come about?

The first commission actually came about more or less by chance. My plan was to launch and develop my own label first. Then a contact reached out in a bit of an emergency and asked if I could develop and produce a collection for another designer. That was my first big job, and it really pushed me. I had to program and produce an entire knitwear collection. It felt like being thrown in at the deep end – and that was exactly what I needed. I just did it, without really knowing what it would feel like, but in hindsight, it was an incredibly valuable experience.

So you never did any advertising?

No, funnily enough, I’ve never actually done any advertising. The projects themselves keep me so busy that I simply don’t have the capacity to also focus on marketing. And knitwear collections are, on the one hand, a completely normal part of the fashion world, but on the other hand, they're also very specialized. I've been incredibly lucky that things have worked out the way they have – but that doesn’t mean it’s always easy. It’s a process – sometimes three steps forward, then two back.

It’s not just about advertising, but more about finding the right people and making genuine connections. I've learned that it doesn't make sense for me to advertise on a broad scale. It’s much more effective to find the people who are truly interested in working together and who share the same values. That’s how my way of working has evolved – often people reach out, and if it feels like a good fit, I take on the project.

But even here I’ve learned that the collaboration itself is what makes the difference. Many people assume that a knitting machine will deliver quick results, but that’s simply not the case. When you work with people who understand the material and the process, the best opportunities often arise – and the work becomes even more fulfilling.

How did you get into fashion?

I studied fashion design at the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Pforzheim for five years. It was a very comprehensive program – we spent a lot of time thinking about clothing, designing, drawing. Art and cultural history, philosophy, and typography were also part of the curriculum. I really appreciated this conceptual and design-oriented approach.

©oHneH/Pauli Beutel/Berlin

©oHneH/Pauli Beutel/Berlin

What advantages does your microfactory offer compared to traditional production?

A major advantage is the creative freedom I have with the machine. In traditional industry, access to such machines is often very limited—they're mainly used as pure production tools. In my case, the machine becomes a creative instrument. For example, I’m currently working on a bridalwear collection with a designer from Amsterdam who already has a good understanding of industrial knitting processes. We were able to get started right away, share ideas, develop structures together, and approach the collection from a design-driven perspective.

It’s a very organic process, with ideas evolving through dialogue. We communicate informally, send each other pictures, coordinate almost daily—and that exchange leads to completely different outcomes than what’s possible in a conventional production chain. Especially in knitwear, tiny details—like a slightly different yarn or stitch structure—can completely change the look of a piece. These nuances can only be explored in close, personal collaboration, and that’s exactly what my microfactory enables.

What does collaboration with clients look like? What can people expect?

Each collaboration is highly individual - it really depends on what the clients bring to the table: their expertise, their vision, and their business model. Some are more experimental and look for custom-made pieces, others produce larger quantities. I adapt accordingly.

Take the Dutch label I mentioned - we’re working through an elaborate development process because they focus on high-end, one-of-a-kind pieces. The production is local, but parts of the finishing are handled by a partner atelier. We coordinate together on how to best divide the work. It always comes down to whether the collaboration makes sense for both sides—technically, time-wise, and personally. That’s something I clarify in an initial conversation. It usually becomes clear pretty quickly: Does this make sense? Are expectations realistic?

If I feel there’s a mismatch or the potential for frustration, I turn down the job. That’s become really important to me.

There’s not much personal information about you online. Would you mind telling us a little more about yourself?

Before founding oHneH, I worked for almost seven years at a local Hamburg fashion label called DFM. I was a designer there and also helped run one of the two stores for three years. The work was very hands-on - custom tailoring, lots of cutting, pattern-making, and sewing. That’s where I realized how much more connected I feel to a product when I’m involved in both the design and the making. Doerte F. Meyer, who founded DFM, gave me a lot of freedom. It was an intense and formative time.

Knitting came into the picture when we had a piece at DFM that we couldn’t realize with cut-and-sew techniques. I thought, “We should really do this in knit.” And then I realized I actually had no idea how to knit it. That frustrated me - I wanted to figure it out. I kept getting rejections from knitting mills - “Not possible,” “Can’t be done.” I thought: “That can’t be true.” I was convinced it had to work. And that’s where it all started.

So it was more of a personal drive than a set plan?

Yes, absolutely. I just wanted to understand it. I had done some knitting during my final collection—giant needles, hand-dyed yarn, very physical, very raw. But this new approach came more from the question: “How far along is 3D in textile printing?” That led me to projects involving hacked knitting machines and 3D printers. But I quickly realized: that doesn’t lead to a viable production process.

Then I came across flat knitting machines -Shima Seiki and Stoll. I just called up Stoll—completely inexperienced. Mr. Knecht said, “If you’re serious, call me back.” And then he gave me the contact for a structural engineer in Brandenburg—in Letschin, near the Polish border.

And that’s where you learned everything about knitting?

Exactly. I just reached out - totally naive. She had two machines, more or less as a private setup, and I kept going there - regularly for two or three years. She taught me the basics. The rest I taught myself step by step - with the Stoll hotline on the phone. They were always a bit puzzled that I’d never taken a course.

Why didn’t you do a training course?

Because I didn’t have a plan. There was no master plan to become a knit technician. I just followed my curiosity. It was only in Brandenburg that I realized how deeply fascinated I was. The software, the machine - it felt like a challenge. I wanted to crack it.

At the same time, I was doing freelance styling jobs to earn money. I had quit DFM without a clear plan but with the thought: “I can always take on projects.” So I rented a tiny prefab apartment in Brandenburg, slept on a camping bed, and spent whole days at the machine. And that’s how I learned.

So it didn’t start as a business idea at all?

Exactly. At first, it was purely a personal interest. The idea of turning it into a business came much later. I just wanted to understand how it works. I still remember something I learned at DFM. My former boss once told me: “You spend so much time working - ideally, you do something you truly enjoy.” That stuck with me. I thought: Yes, that’s true. How do I actually want to spend my time?

What values and beliefs are especially important to you - and how do they show up in your work?

One key value for me is deep, lasting engagement with something. I mean that in the literal sense - something that leaves an impression on you. I really admire people who dive deeply into their subject. I think that kind of focus is valuable, also in human relationships. Knowledge gained through experience is something I deeply respect.

A good example: Yesterday I had a call with Ms. Meier from Stoll - she works in their Fashion & Technology division. I wanted to know something about transparent yarns. And in just five minutes, she gave me insights that would’ve taken me hours to research. I find it amazing when you have access to people like that. And I think knowledge that comes from experience is a value in and of itself.

Another core value for me is equality. For example, I do all steps of the production myself - including tasks that are often outsourced, like linking (Ketteln in German). It’s very time-consuming and usually done abroad as piecework. But I wanted to learn it myself - because I believe that every part of the process should be seen as equally valuable, not ranked in a hierarchy.

And your label oHneH is gender-neutral - that fits really well with the theme of equality, doesn’t it?

Yes, absolutely. I find it more exciting when clothing doesn’t already declare who it’s for. That openness is what draws me in.

©Mone Unmüßig

©Mone Unmüßig

What challenges did you face when founding and building your label?

There were many challenges—and in reality, they never fully stop. Launching my label and establishing my MicroFactory were deeply formative experiences. Initially, I imagined a compact production system: an order comes in, I program the machine, produce the piece, package it, and ship it. Back then, I didn’t call it a “MicroFactory”; I simply thought of it as a mini-factory working to order.

Today, I see similar concepts emerging elsewhere - such as with Goran Sidjimovski or Luisa Lauber, at the VORN Fashion Hub in Berlin, or at FABRIC in Hamburg. That’s exciting, because it shows the industry is shifting.

One of the greatest challenges has been - and still is - making individualized production economically viable. I can’t have a €120,000 machine sitting there if someone approaches me and says, “I’d like a scarf,” without understanding the effort involved. To produce a single piece can take several days - from development to execution - and the market often isn’t prepared to pay for that.

From the very beginning, my aim was to make industrial knitting more accessible. It felt like a shame that such technology was reserved for large-scale production, limiting the possibilities for many designers. I’m still exploring ways to make it more accessible - without sacrificing my creative freedom. A scalable business model often means specialization or giving up creative control, and I don’t want that. I want to design, not just produce.

How did you manage the transition into knitted production?

To be honest, I had almost no experience with industrial knitting at first. Even so, I wanted to create a high-quality product, which is why I deliberately chose luxurious yarns like long-fiber baby alpaca and a silk–merino–alpaca blend. With the ADF machine, I was able to produce plated fine knits - technically demanding, but incredibly motivating. I was immediately fascinated by what I could achieve.

For my label oHneH, I now produce almost exclusively single pieces. I don’t have capacity for traditional marketing or distribution, so I finance the label largely through custom orders. Entering conventional retail is challenging for me, as most margin structures don’t reflect the true value of my production. I much prefer direct relationships with my clients. I want to build long-term collaborations based on trust, understanding, and shared design values. That, to me, is more sustainable - both economically and personally.

©oHneH/ Pauli Beutel/Berlin

What was the process like for getting a KfW loan?

Thanks to previous income from my styling jobs, I was able to show solid revenue. With the help of a tax advisor, I created a business plan and applied through my bank. The meeting with the bank lasted around three hours. A few weeks later, I received approval. Since I didn’t have enough equity, I also needed a guarantee. I applied to the Hamburg Guarantee Bank and had another meeting - this time with representatives from both the bank and the guarantee institution. In the end, I was approved.

How did you become a member of FABRIC – Future Fashion Lab in Hamburg?

A designer from Hamburg told me about FABRIC, which was initiated by the Hamburg Kreativgesellschaft. I signed up right away and was involved from the very beginning - even when the space was still under construction. The idea of combining design, production, and sales of sustainable fashion in one place really resonated with me. I wanted to contribute actively and I can see that something genuinely good is developing there.

What, in your opinion, makes the fashion scene in Hamburg unique compared to other cities?

Hamburg doesn’t necessarily have the reputation of being a traditional fashion capital. Personally, I don’t automatically associate fashion with Hamburg. But there is a fashion scene here - albeit one that’s a bit more understated and hidden. And that’s part of its charm. Over the years, I’ve met many great people working in fashion in Hamburg. Compared to other cities, the scene here feels almost familial - people know each other, it’s more familiar, friendly, even cozy in a way.

I remember collaborative events or special sales with other Hamburg-based designers when I was still working for Doerte - there was always a warm, supportive atmosphere. At the same time, I wasn’t really active in Hamburg’s fashion scene for a long time. I was more involved in technical networks or working one-on-one with other creatives. One reason I’m active at FABRIC now is that I want to become more visible and make my work more accessible to designers in Hamburg. I want to be a place where ideas can be realized, where people come together to create and produce collaboratively.

What advice would you give your younger self if you had the chance?

I once wrote down the phrase “Choose wisely” - and then I crossed out “wisely.” For me, it’s less about making the perfect decision and more about consciously making a choice at all. Looking back, I would tell myself to be more open to collaboration and working with others. I did a lot on my own for a long time - which was fine - but now I know how enriching it can be to work together.

I would also say: Trust the process. I used to have the urge to implement specific ideas exactly as imagined. Today, I understand much better that things evolve, that paths aren’t linear, and that there’s great strength in that. Your own approach can shift, can take shape in ways you hadn’t originally planned - as long as it stays in motion.

What do you think are the biggest challenges facing the fashion industry in the coming years?

The fashion industry is facing a fundamental transformation - it has to restructure. And it’s about much more than fashion alone: political, environmental, and societal boundaries are all at play. The current systems need to be broken down and reimagined - which is an enormous challenge because so many interdependencies are involved. The sheer amount of clothing being produced today is simply too much. We need less - but also new ideas and creative approaches.

One of the biggest challenges I see is the tension between sustainability and the inherently extravagant, expressive nature of fashion. Fashion is about vision, expression, sometimes escapism - it thrives on excess, on imagination. We must not lose that just because we’re focusing on necessary reduction.

I recently watched the Valentino Haute Couture show and was absolutely blown away. The craftsmanship, the beauty - it showed what fashion can be. It would be a shame if all that remained was functional, purely rational clothing. Of course, the industry must conserve resources - but it shouldn’t lose its dreamlike quality. We don’t all have to walk around in plain linen shirts. Fashion should still be allowed to express fantasy and creativity.

©Mone Unmüßig

©Mone Unmüßig

What projects or collaborations would you like to pursue in the future?

I want to continue developing my label oHneH and further expand my MicroFactory - there’s still so much in the early stages. I’m hoping for interesting projects and people to collaborate with. It doesn’t have to be specific names - I’m more drawn to exciting ideas and designers who are open to technical experimentation and collaborative work.

For example, I love it when technical challenges force me to rethink my approach. When I worked with the Dutch label, I really felt like I took a big leap - because of complex knitting solutions like integrated button loops, which really pushed me. That’s what motivates me: to improve, to become more versatile, to realize new ideas. I want to grow - not just for myself, but also to inspire and spark ideas in others.